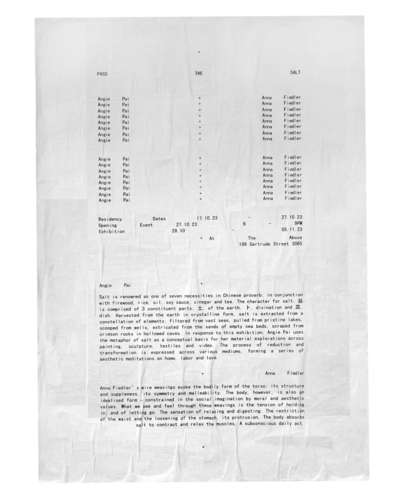

Pass the Salt

Exhibition Essay by Hannah Wu

腌, yān, to pickle, to cure

Angie emerges from behind a gargantuan jar of pale sauerkraut, which has been stewing in her kitchen and drifting pungent fumes through her house for the past few weeks. Like a magician, comedically procuring an endless array of objects from a magic hat, Angie reaches over and pulls 10 additional jars from out behind her. She adjusts them in a row in front of her phone camera, which is precariously balanced between a tea egg, a bowl of noodles, a cantaloupe melon and a large silver cleaver.

It is the middle of the 2020 covid lockdown, everyone is absolutely fucking miserable, and Angie has somehow managed to start her 5th new hyperfixation hobby. We are video calling for the third time that day, and it has reached the 6th cursed hour of being on the phone with each other.

“You freak. Why have you made so much sauerkraut?” I ask, adjusting the camera to better see the glow of her face, emitting from my screen. “Ferment cabbage, not feelings!” she yells gleefully, laughing with the kind of hysteria that would send Sigmund Freud into cardiac arrest.

For those who are familiar, Angie possesses a signature laugh which rings at a decibel caught somewhere between a roar and a typhoon. Her laughter is cacophonous; it balloons through the room, so that the air and the people around it are inflated with its joy. My phone, my head and the room too, gives the impression of expanding when she laughs.

“And… So I can give it to all my friends! Duh. I wouldn’t just make sauerkraut for myself,” she continues. I ask Angie how she made all the sauerkraut, to which she explains that it requires layering salt and cabbage into thick folds, compressing the air in the jar and patiently tending to the ferment over several weeks. “It’s simple: all it really takes is salt, cabbage and care.”

Salt is simultaneously the preservation agent which protects the cabbage from decay, while it is also the alchemizing agent of the fermentation process; the spell that converts the cabbage into sauerkraut. Salt is at once protective and transformative, allowing the properties of the original source to retain its essence, while also allowing for change to occur over time. This figuration, perhaps, is also what we can use to describe the qualities of what we come to know as friendship, and as a corollary of this, of love. “Watch me eat!” she screeches.

Angie then proceeds to perform an ASMR mukbang for me on camera; clipping the sauerkraut with a pair of chopsticks into her bowl and threading noodles into her mouth. After slurping the sour soup, she holds the glinting cleaver high and hacks the cantaloupe melon into pieces. “I wish we were having dinner parties together again, but this will do for now,” she laughs.

盐, yán, salt

Salt is renowned as one of seven necessities in Chinese proverb; in conjunction with firewood, rice, oil, soy sauce, vinegar and tea. As a commodity, salt was also once a currency in ancient China, a precious resource which was used in trade, exchange and barter. Salt is also that which distinguishes water from sweat, as a marker of the labour that leaks from our bodies when we work.

The character for 盐 is comprised of 3 constituent parts; 土,of the earth, 卜, divination and 皿, dish. Harvested from the earth in crystalline form, salt is extracted from a constellation of elements; filtered from vast seas, pulled from pristine lakes, scooped from wells, extricated from the sands of empty sea beds, scraped from crimson rocks in hollowed caves. Consistent in these extraction methods is a process of reduction; an alchemical process in which force is exerted on the substance through evaporation; through a process of disappearance. Evaporation can be understood as a conversion of form that moves from a liquid to a solid state; and perhaps this is akin to a kind of divination, a kind of alchemy, in which the properties of matter are transfigured, so that only residue remains. Once harvested to use in a dish, salt is also that which grounds food as substantial, as distinguished from sweetness, which might be understood as excess.

In Chinese, salt “盐” (yán), is a homophone for “严” (yán), which means, to be serious. This is to say, that I am of the belief that there are 2 kinds of people in this world: people who are “盐, salt”, or people who are “严, serious”. For people who are “盐”, they are the salt; the additional taste to the meal that will always improve it, a necessity that adds liveliness to every context. In Chinese cooking, salt is not sprinkled on after a meal, but added at the beginning of the cooking process, so that its flavour becomes essential to the dish. Salt is the main event, while it is always complimentary and isomorphic to its counterparts; the magic that transforms the dish through combination and play. For the latter, of people who are “严”, they are solemn, self-possessing, and always armed with a deep pensiveness that is reserved at its heart. They are always profound, they carry an earnest gravity to their speech, which holds the weight of the world. 严 also means “closely sealed”, and comprises of the character 厂, meaning factory, or work, to designate labour. People who are “严” are associated with discipline, which might also be thought of as the layered consistency of labour.

In her rust series, Pai layers various materials to construct her large canvases; paint, plaster, glue and finally, bronze powder. Through the sedimentation of materials, her work accrues textural layers, which are bonded in unity on the surface of the painting. Each layer is a record of history, the solidification of her artistic labour, enacted upon the canvas. The final layer of bronze is then coated with saline salt water, engaging in a process of degradation so that the canvas literally rusts. “It feels as if I am fermenting the canvases with salt over time, so that they are just big fermented paintings,” Angie explains to me. Developed from her white paintings over the span of a decade of experimentation, her rust paintings are the “post-fermentation”; a record of the material transformation from the originary genesis of her white works. These paintings possess the spirit of both 盐 and 严; imbued with the play of salt, while acting as a disciplined document of her work over many years.